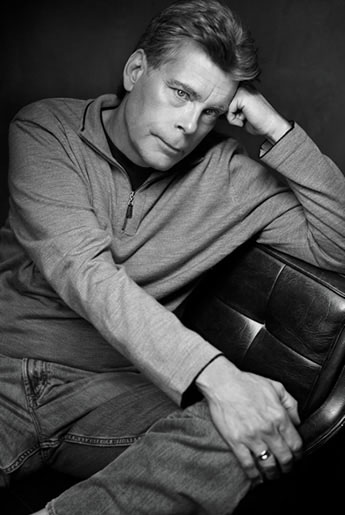

I always disregarded the works of Stephen King. Despite (or perhaps due to) his wild popularity, I always thought of him as a “sell-out,” an author willing to rely on cheap cliffhangers and deliciously revolting subject matter to keep the reading masses turning page after gruesome page. Plus, I don’t enjoy being scared. Haunted houses and the Saw movies are on my list of things to avoid, so why would I read a book of the same ilk?

I always disregarded the works of Stephen King. Despite (or perhaps due to) his wild popularity, I always thought of him as a “sell-out,” an author willing to rely on cheap cliffhangers and deliciously revolting subject matter to keep the reading masses turning page after gruesome page. Plus, I don’t enjoy being scared. Haunted houses and the Saw movies are on my list of things to avoid, so why would I read a book of the same ilk?

My father, on the other hand, is a big Stephen King fan. I believe he’s read just about every King book there is and pretty much enjoyed them all. He would often recommend the books to me after he was done, but at that time I only made room on my bookshelf for books considered “literary” or “classic”.

Just a few weeks ago, however, I found a copy of King’s newest book, a collection of short stories calledFull Dark, No Stars, on my kitchen counter. I was intrigued, because a collection of short stories seems a vessel more suited to noble literature than trashy horror. I also recalled a college professor whom I greatly admired had recommended King’s work (she was reading Carrie), so I gave it a shot and read the first story, “1922.”

I have to admit: the book wouldn’t let me put it down (as if it possessed me). I read all 128 pages in two sittings, and it wasn’t the result of gratuitous cliffhangers as I imagined. The events of the tale were gripping, but what kept me reading was the narrator’s voice. Within the first few sentences, Wilfred LeLand James, or “Wilf,” makes it clear this story is his confession of the murder of his wife, Arlette. Throughout the narrative, my feelings towards him oscillated between revulsion and pity. The perversity of his thoughts and deeds, though horrifying, were grounded in humanness, and through his telling I became thoroughly acquainted with his mind, a mind quivering with fear, paralyzed by obstinacy, and wracked by guilt.

Near the beginning of his confession Wilf states, “I believe that there is another man inside every man, a stranger, a Conniving Man.”

Throughout the story, Wilf refers to things the Conniving Man does or says and we come to see this evil figure as a separate entity, an evil twin or counterpart. It seems it’s human nature to feel like this when we make mistakes in our own lives; however, the story’s chilling finale is a reminder that cannot ignore the evil inside (or it will lead to our destruction).

I have to put my foot in my mouth, because I found “1922” haunting, provocative, and (dare I say) literary. Stephen King will probably never be my favorite writer, since I am a wimp when it comes to things that go bump in the night, but I have learned not to judge a work by its genre. It is the writer (and sometimes the lesson we learn from his demented character) that truly makes the work.