Andrew Wyeth’s art is quiet. In contrast to many of his contemporaries, whose works scream out for attention through bright colors and bold shapes (Rothko and Mondrian), or seduce with lush layers of paint and incomprehensible abstractions (Pollock and de Kooning), Wyeth’s paintings are subtle. They whisper their intention to the viewer. Muted colors and barren landscapes mark Wyeth’s most recognizable works, but all of his paintings share a common sense of stark intimacy.

Andrew Wyeth’s art is quiet. In contrast to many of his contemporaries, whose works scream out for attention through bright colors and bold shapes (Rothko and Mondrian), or seduce with lush layers of paint and incomprehensible abstractions (Pollock and de Kooning), Wyeth’s paintings are subtle. They whisper their intention to the viewer. Muted colors and barren landscapes mark Wyeth’s most recognizable works, but all of his paintings share a common sense of stark intimacy.

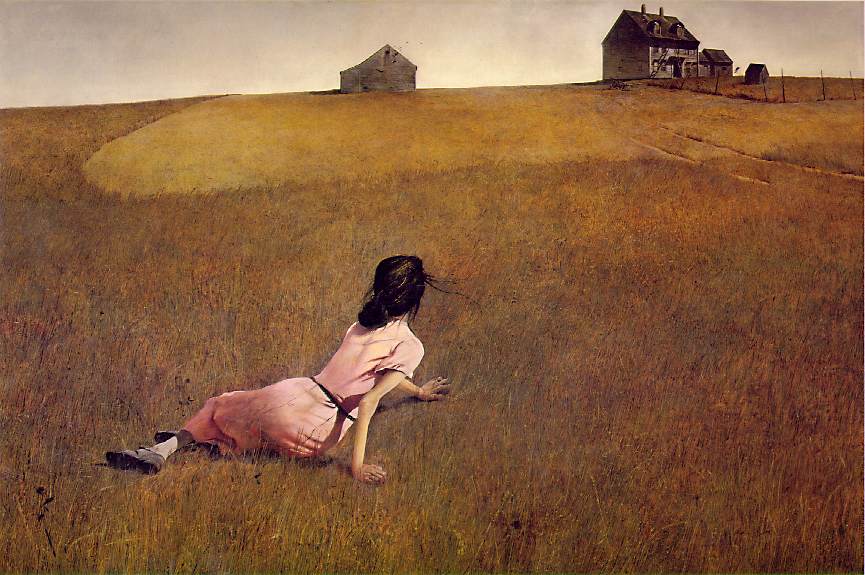

I’m not the only one who feels this way about Wyeth’s art. Earlier this month, the house in Maine depicted in his most famous work, Christiana’s World (above), was named a national landmark. “It’s now affirmation that it’s an American icon,” said Christropher Brownawell, executive director of the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, in an interview with the Associated Press. On July 1, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, announced that The Olson House, along with 14 other locations, is now officially recognized by the U.S. Government.

The news shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone familiar with American art. Though he didn’t fit into any of the major artistic movements of the 1940s, Wyeth was an exceedingly popular artist; something about his pieces felt recognizable in that post-depression era. I like to think it’s because his scenes are so touching and instill an immediate familiarity in the viewer: we can’t help but feel as though we’ve been there. His style may not have been as flashy as that of his contemporaries, but Wyeth’s work has long been recognized as different, respected in its own right. Quietly, it captured the era.

Painted in 1948, Christina’s World was titled after the woman who inspired the image, Wyeth’s neighbor, Christina Olson. But while the painting is ostensibly about her, Wyeth did not use Olson as a primary model. Instead, he called upon his wife to pose for the scene, recreating the moment he looked out the window and saw his neighbor, who suffered from polio, making her slow crawl across the yard. Looking at this painting, I believe I can see the love he had for his wife, and the sad respect he had for his subject. The landscape is bleak and muted, but there is a tenderness in the way Wyeth depicts Olson. I feel instinctively, as many have before me, that this piece captures something essentially human, something even bigger than the scene, more important than the farmhouse.

Though I’ve seen the painting in person—it hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York—I haven’t yet visited the location in Cushing, Maine. But somehow, I feel as though I have been there, as though the moment he depicted is not in a place or a time, but happening constantly. It’s an ineffable thing, but one I’m not quite ready to mar with a visit to the actual location. But despite my personal reluctance, I’m happy to know that no matter what, the Olson House will be there when I’m ready to see it.