My recent trip to Charleston, South Carolina was incredible. I have wanted to visit the city for years and I was delighted to partake in historical tours, hearing tales of the American Revolution and the Civil War, leisurely strolls and an abundance of incredible food and drink. The week-long getaway was exactly what the doctor ordered to cure the stresses, anxieties, and routine of day-to-day life.

But despite the feeling of freedom and blissful contentment at having no responsibilities, I found myself falling victim to that same sneaky trap that so many American travelers fall into: I was preoccupied with work.

Now let me say, for the record, that I love working with Literary Traveler. It’s a great company with great people and often when I’m working there it doesn’t feel like work at all. This preoccupation may have been due, in part, to the knowledge that our Kickstarter was going live while I was away. It was weighing on my mind that if we were successful in meeting our funding goal we would be shooting our TV pilot and, that if we weren’t, we would be back to square one. The pilot episode and the Kickstarter campaign were just too big to put out of my mind.

Now, Charleston is a city rich with history and old-world elegance. One of the most preserved cities in the U.S., it looks today much as it did one-hundred years ago (besides the paved streets, upscale shopping boutiques and foodie hotspots). Meandering past war monuments, hotels and houses dating back as far as the 1800s, it was easy to imagine a world long ago and far away. But my mind wasn’t on war and it wasn’t going back that far. What I kept finding myself thinking about was The Great Gatsby, Nick, Daisy and Jordan, and of the roaring twenties.

Specifically, what I was wondering was whether that flapper-essential dance, the Charleston, was in fact named for my destination city. After digging up a little research, I found that the light and carefree dance had some dark history behind it.

Yes, the dance is named after the coastal landmark city. To be more precise, it is named for the show tune it was first danced to, “The Charleston,” by James P. Johnson, which premiered in the 1923 Broadway show Runnin’ Wild. The show was one of the most popular of the decade and created widespread love of the Charleston dance by women around the country who wanted to kick up their heels, flap their arms and let loose.

But long before the glamorized show-dance ever made its Broadway debut, it was being performed, though in a far less choreographed fashion, by African and African-American slaves. The Charleston, you see, is said to be based on the “Juba” dance, which originated in West Africa and was brought to America during one of our most shameful times in history.

The city of Charleston was a hub in the slave trade, housing an abundance of plantations for which slave labor was used and Ryan’s Mart, one of the most well-known slave auction centers ever to exist. Enslaved Africans and African-Americans have passed a number of our cultural treasures along including gospel, blues, and jazz music and the dancing to go with them. The Juba, sometimes called the “Hambone” or “Pattin’ Juba,” was usually danced in groups and consisted of slapping, clapping, and stomping in rhythm while rotating in a counterclockwise circle. The slaves were not allowed to use drums or other rhythmic instruments for fear that they were communicating with each other through the music, so they made their own rhythm using their bodies. This may not sound like the Charleston you have seen, but much of what has become jazz and tap dance originated from these steps.

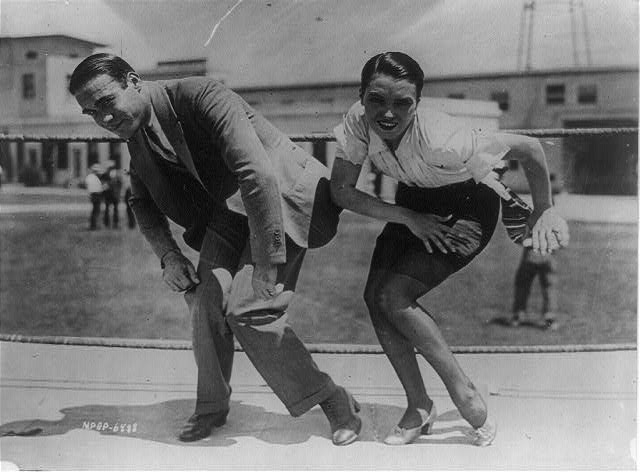

Similarly, the women of the 1920s were using dance to express ideals that had once been forbidden and taboo: freedom, fun, carelessness and independence. As a matter of fact, the Charleston was outlawed in many places during the 20s because it was seen as crude and scandalous. It is interesting to see how these two groups of people, the slaves in the direst of circumstances and American flappers, many of whom were privileged monetarily and lived seemingly happy and easy lives, do relate to one another. Their environments were so ostensibly different, and yet, the feeling of being stifled, caged, confined, existed inside them all. The dances of the day, the Juba and the Charleston, helped each group to cope with their circumstances and feelings and enabled genuine creative expression.

I wonder if Daisy ever thought about this.