Lovers of machinery – masters of cogs and wheels – enjoy the knowledge that every little piece is essential for a device to work. Hugo Cabret belongs to this mechanical school of philosophy. While he hides in the churning spirals of a giant clock, he relentlessly works on his secret project. If he stops, it seems, so will time.

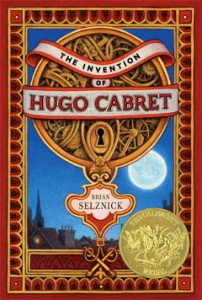

I first discovered Hugo’s story in the fall of 2008 when a good friend was writing a review and insisted that I read the book. Not so much reading was necessary because the pictures drive the tale. Until that moment, I had not quite warmed to the graphic novel phenomena. I enjoyed crafting the visuals of a story in my own imagination versus seeing them outright. But The Invention of Hugo Cabret changed my mind. Hugo’s story had to be told with a certain amount of quiet suspense, like a silent film. I was not surprised to hear that a movie was on the horizon.

Martin Scorsese effortlessly translates The Invention of Hugo Cabret to the screen with the cinematographic dexterity that he is praised for time and time again. Brian Selznick’s illustrations, dark and fraught with anticipation, and his elegantly crafted story provided the kind of visuals and pacing that any filmmaker would be thrilled to reanimate. The movie, although a bit slow-paced, is to me a perfect execution–a stuck landing after a swirling gymnastic feat.

Selznick says the story was a film to him all along. He described his delight at Scorsese’s adaptation in a San Diego Union-Tribune interview this past September: “People on the set were walking around with copies of the book. It was really a thrill to see how respectful everybody was.” The son of David O. Selznick, a well-known Hollywood producer of the classics “Rebecca” and “Gone With the Wind,” Selznick’s style of storytelling is intrinsically suited to the screen.

The movie, like the graphic novel, is an homage to a once-forgotten pioneer of cinematography. The digital medium is able to precisely demonstrate what Selznick describes. Scorsese recreates clips by the magical Georges Méliès and educates the audience on his brilliance. The dreamlike story as a whole is irresistible. Despite only rare moments of what’s-going-to-happen tension, I sat on the edge of my seat in the theater, not wanting to blink for fear of missing a minute of the magic.

Selznick, 45, released his second book, Wonderstruck, earlier this fall. The story is of a girl who feels drawn to a famous actress–her story told entirely in pictures–and a boy who longs for a lost father–his tale told only in words. The two weave together in the end. So far, reviews have been sparkling, and I cannot wait to see where Selznick takes us next. With any luck, Scorsese will bring Wonderstruck to the big screen as well.